July Newsletter Article

Written by: Seanicaa Edwards Herron, Agricultural Economist, Freedmen Heirs Foundation Executive Director

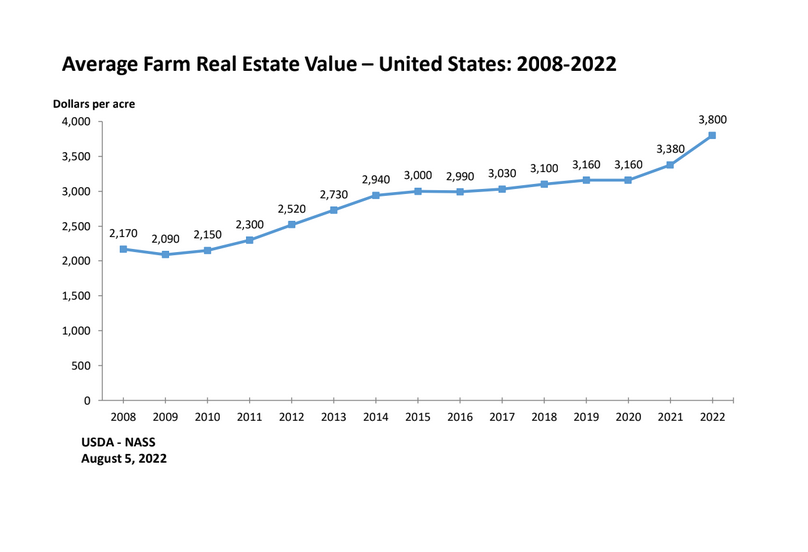

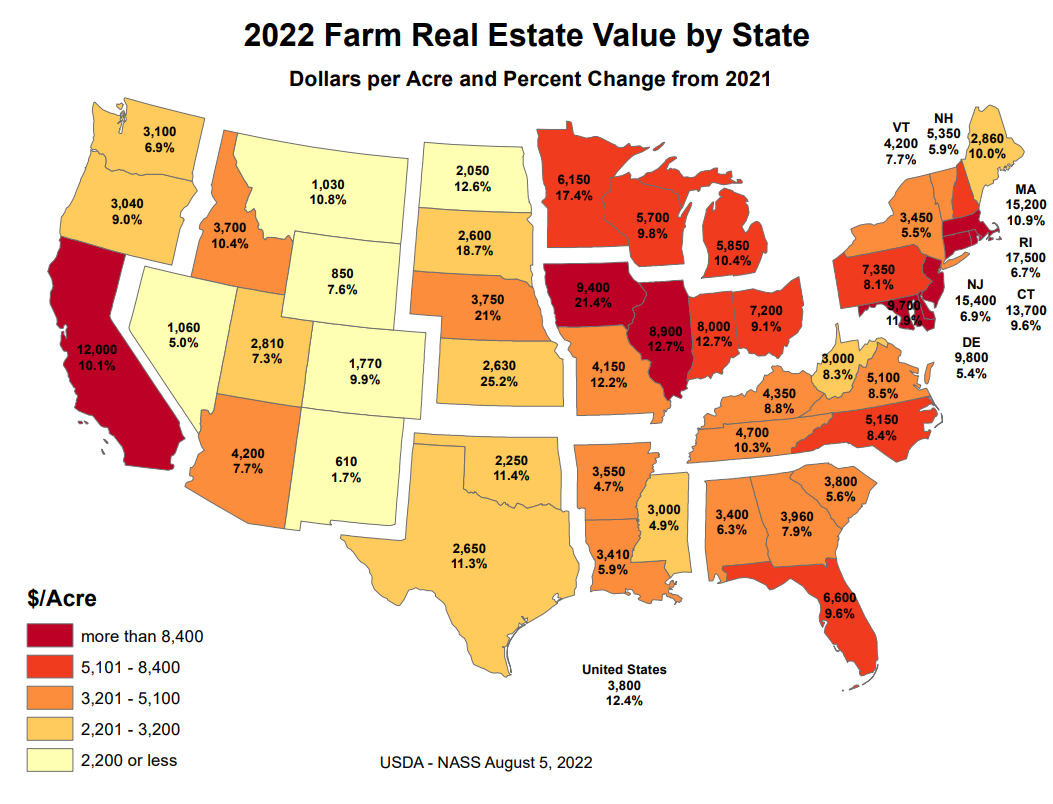

Agricultural farmland is an appreciating asset and principal source of collateral for farm loans, and it is critical to the overall financial well-being of farmers and landowners. Currently, farmland prices remain at historic levels and are forecast to increase in the long-term. According to USDA’s Land Values report, the value of all land and buildings on farms, averaged $3,800 per acre for 2022, up 12.4 percent from 2021. Cropland value averaged $5,050 per acre, 14.3 percent higher than the previous year while pasture value averaged $1,650 per acre, an increase of 11.5 percent from 2021. It’s also worth noting that agricultural production is a major use of land, accounting for roughly 52 percent of the U.S. land base. With a value of $2.55 trillion in 2019, the value of farm real estate (land and structures) accounted for over 80 percent of the total value of the U.S. farm sector total assets. (See data on Major Land Uses).

Moreover, there has been a significant increase in the purchase of farmland from deep pocket investors (domestic and international), private equity funds, family foundations, real estate developers, and pension funds, pricing farmers and landowner out of the market. This is particularly problematic for minority and beginning farmers and landowners. Houston… we have a problem!

Land acquisition and retention are key components to building generational wealth and closing the equity gap for Black farmers and landowners. Over the last century, Black farmers and landowners have lost more than 12 million acres of farmland. In a study conducted by Francis, Hamilton, et al (2022) the value of the Black land loss and its income from 1920-1997 totals approximately $326 billion. It is important to note that this estimate is conservative. The true impact is far greater than estimated, as rising land and commodity prices over the last 26 years were not captured along with other economic factors. Nonetheless, this historic land loss represents a massive transfer of wealth from the Black community with repercussions still being felt to this day. Another emerging trend that is reshaping the face of U.S. agriculture is the aging population of farmers, which will result in a massive transfer of farmland over the next two decades. With such a significant shift on the horizon, it’s imperative that minority and socially disadvantaged farmers and landowners have succession and estate plans, wills, and trusts in place to evade “heir property” issues and further displacement from family land.

So what can be done to fix this problem of limited access to farmland, particularly for Black and historically underserved farmers? USDA’s current Increasing Land, Capital, and Market Access (Increasing Land Access) Program is a start but won’t solve the problem in its entirety. There must be explicit legislation passed in the 2023 Farm Bill that provides more protections for current farmland owners and adequate funding for beginning farmers, especially socially disadvantaged producers to access land. However, non-traditional mechanisms need to be developed to alleviate the financial pressures of obtaining farmland. Farmland Investment Funds and REITs are common ways of owning and investing in farmland. While there have been funds created with the express purpose of converting farmland to organic production, there has never been an investment fund with the explicit purpose of acquiring farmland to enable sustainably managed Black-owned farms at scale. A fund of this type, scope, and magnitude would be an integral component in reversing the trend of Black land loss.

While there could be a component of philanthropy that supports this work, a better strategy for mobilizing capital would be to understand the components of financial returns from agricultural land—equity growth of the land, tax benefits of farmland, and income generated from farming activities/land stewardship—and then to assign those financial gains to farm operators and community stakeholders (including farmworkers).

A special purpose vehicle (SPV) to accomplish this endeavor could unlock capital investment and enable Black farmers to access land that would otherwise be unaffordable. It would also enable younger people or those from nontraditional farming backgrounds, such as Black veterans to consider farming as a viable profession. Once created, the structure could be used to support farmland investments for other historically marginalized groups, young farmers, and others who have largely been unable to participate fully in the agricultural sector.